Egg Rolling Down the White House Lawn in the U.S.

Every spring, the South Lawn of the White House transforms into a playground of pastel eggs, wooden spoons, and exuberant children—but this isn’t just another Easter egg hunt. The White House Easter Egg Roll is one of the oldest and most peculiar presidential traditions in the United States, with roots stretching all the way back to 1878. That year, President Rutherford B. Hayes officially opened the White House grounds to children after Congress banned egg rolling on Capitol Hill to protect its manicured lawns. In a move that combined political savvy with childlike whimsy, Hayes turned a legislative crackdown into a public celebration that continues to this day.

But here’s the twist—this wasn’t the first time kids had rolled eggs in D.C. Informal gatherings had taken place as early as the Lincoln administration, and by the 1870s, the Capitol’s west grounds had become a chaotic Easter Monday hotspot. After the ban, Hayes’ invitation to the White House turned the event into an annual tradition that only grew in pageantry. Over the years, First Ladies have added their own flair—Pat Nixon introduced the now-famous egg roll races in 1974, and Nancy Reagan began the tradition of gifting souvenir wooden eggs signed by the President and First Lady in 1981.

The event has weathered its share of interruptions—World Wars, post-war rationing, and even the COVID-19 pandemic—but it always bounces back. Today, more than 30,000 guests attend the festivity, which now includes live music, costumed characters, and storytelling sessions. What began as a workaround for egg-rolling bans has evolved into a celebration of spring, civic openness, and—perhaps most surprisingly—presidential hospitality. It’s not every day you get to roll an egg where world leaders walk.

Exploding Easter Carts in Florence, Italy

Florence isn’t exactly known for subtlety, and Easter Sunday is no exception. Every year, thousands gather in Piazza del Duomo to witness a centuries-old tradition that’s equal parts religious ritual and pyrotechnic spectacle: the Scoppio del Carro, or “Explosion of the Cart.” At first blush, it might look like a medieval prank gone gloriously wrong—a 30-foot-tall wooden cart rigged with fireworks, pulled by white oxen through cobblestone streets, only to be blown sky-high in front of the city’s cathedral. But behind the bangs and booms lies a story rooted in Crusader glory and sacred symbolism.

The tradition dates back to 1097, during the First Crusade, when Pazzino de’ Pazzi, a Florentine knight, became the first Christian to scale the walls of Jerusalem. As a reward for his bravery, he received three flints from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre—yes, actual stones from Christ’s reputed burial site. These relics were brought back to Florence and used to spark a “holy fire,” which eventually became the spiritual centerpiece of the Easter celebration. By the late 15th century, this evolved into the explosive display we know today. At the climax of Easter Mass, the Archbishop lights a dove-shaped rocket—called the Colombina—which zips along a wire from the altar to the cart outside. If it successfully ignites the fireworks, it’s believed to bless the city with a year of good harvest, civic fortune, and divine favor.

What makes the Scoppio del Carro remarkable isn’t just the fireworks—it’s the way it fuses faith, folklore, and Florentine pride into a single, thunderous moment. It’s a ritual that’s been uninterrupted for over 500 years, even surviving wars and political upheavals. And while it may look like a Renaissance-era prank to the uninitiated, to Florentines, it’s a sacred spark that lights up both sky and soul.

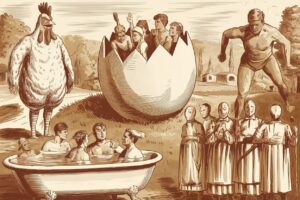

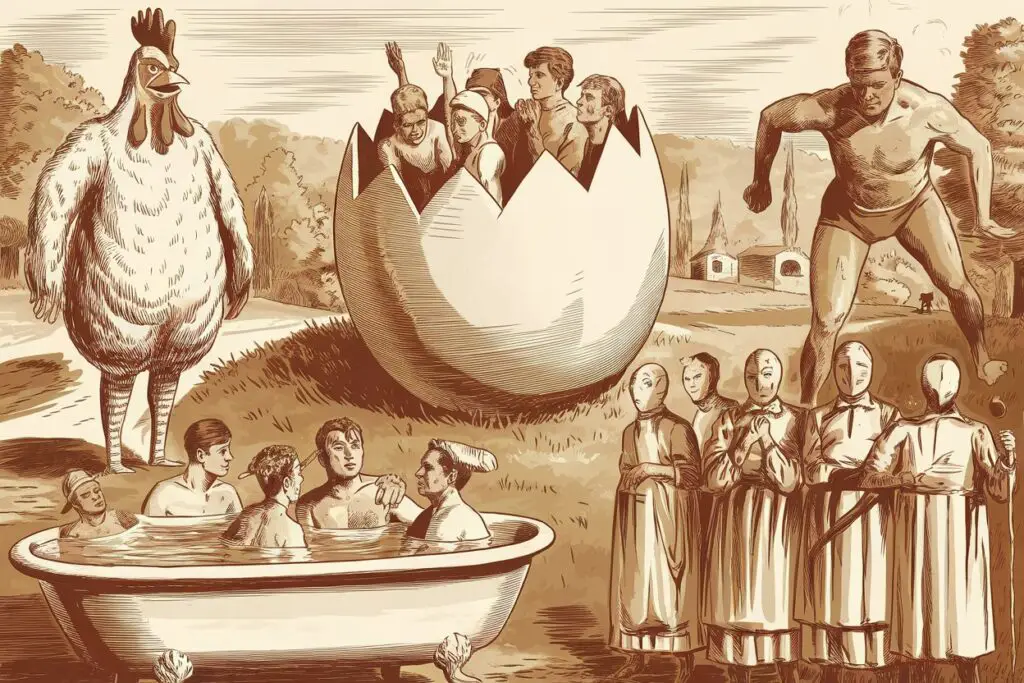

Whipping Women with Willow Branches in the Czech Republic

At first glance, the Czech tradition of lightly whipping women with willow branches on Easter Monday might sound like a chapter from a medieval prank book. But pomlázka, as it’s known locally, is no joke—it’s a centuries-old folk custom rooted in pre-Christian fertility rites and still practiced in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. According to tradition, men and boys braid fresh willow rods into decorative whips, often festooned with colorful ribbons, and gently lash the legs of women in exchange for painted eggs, sweets, or shots of plum brandy called slivovice. The symbolism? The vitality of the willow tree is believed to transfer health, youth, and fertility to the recipient for the year ahead.

But here’s the twist: while some see it as a lighthearted rite of spring, others—especially women—view the practice as outdated or invasive. A 2023 survey revealed that approximately 80% of Czech women dislike the tradition, and many actively avoid it, citing discomfort, embarrassment, or even bruises. Still, the ritual remains surprisingly widespread, with about 60% of Czech households participating in some form. In rural areas, groups of men may travel from house to house to “whip,” while in urban centers like Prague, the custom is often confined to family settings and performed more symbolically.

The endurance of pomlázka underscores a broader tension in modern Czech society: the desire to preserve cultural heritage versus the need to adapt traditions to contemporary values. While younger generations increasingly choose more playful or consensual versions of the ritual, the debate it stirs each spring is a vivid reminder of how folk customs can outlive their original meanings—and sometimes, their welcome.

Dressing Up as Witches in Sweden and Finland

Every spring, just as tulips begin to bloom and chocolate bunnies line store shelves, children in Sweden and Finland don something far less pastel: ragged shawls, painted freckles, and crooked brooms. No, it’s not Halloween arriving early—it’s one of Northern Europe’s most curious Easter customs, where kids dress up as witches and go door to door asking for treats. Known as påskkärringar in Sweden and virpominen in Finland, the tradition blends centuries of folklore, religious symbolism, and a dash of good old-fashioned mischief.

The roots of this quirky tradition aren’t just playful—they’re steeped in centuries-old superstition. In 17th-century Sweden, widespread fear of witches led to brutal witch hunts, with over 200 women executed and the final witchcraft death sentence handed down as late as 1704. People believed that during Holy Week, especially on Maundy Thursday, witches flew to a mythical island called Blåkulla (Blockula) to consort with the Devil. To protect themselves, villagers would hide brooms, lock barns, and light bonfires—some of which still burn today as symbolic witch deterrents.

Over time, this fearsome folklore softened into a child-friendly ritual. In modern Finland, children carry decorated willow branches and chant blessings like, “Virvon, varvon, tuoreeks terveeks…”—a poetic wish for good health in exchange for candy or coins. The branches themselves harken back to Orthodox Christian traditions, symbolizing the palms of Palm Sunday. In Sweden, it’s more of a costumed romp, with kids dressed as old hags collecting sweets in copper kettles, echoing the Halloween-style trick-or-treating.

In both countries, what began as a fearful response to dark folklore has evolved into a charming rite of spring. It’s a reminder that even the most ominous legends can, over time, become celebrations of community, imagination, and a little bit of sugar-fueled fun.

Water Fights in Poland on Easter Monday (Śmigus-Dyngus)

If you happen to be in Poland the day after Easter, don’t be surprised if someone throws a bucket of water on you—and no, it’s not a prank. It’s Śmigus-Dyngus, or Wet Monday, a centuries-old tradition that turns the country into a spontaneous water park. Originally, this custom had little to do with mischief and everything to do with ancient pagan rites of purification and fertility. In early Slavic spring rituals, water symbolized renewal and a good harvest, and young men would sprinkle (or sometimes douse) women with water to bless them with health and fertility for the coming year.

By the 15th century, this ritual had blended with Christian Easter celebrations, marking a joyful contrast to the solemnity of Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Over time, the symbolic sprinkling became more theatrical—buckets replaced delicate droplets, and in recent decades, water balloons and squirt guns have entered the fray. According to tradition, girls could offer hand-decorated Easter eggs, called pisanki, to avoid a soaking—though that rarely works today.

Modern Śmigus-Dyngus is more egalitarian: everyone, regardless of age or gender, is fair game. In cities like Kraków and Warsaw, the festivities can resemble full-blown water battles, with even fire trucks joining in. It’s messy, it’s loud—and it’s one of the most exuberant ways a nation celebrates the arrival of spring. For a deeper dive into the history and cultural significance of Śmigus-Dyngus.