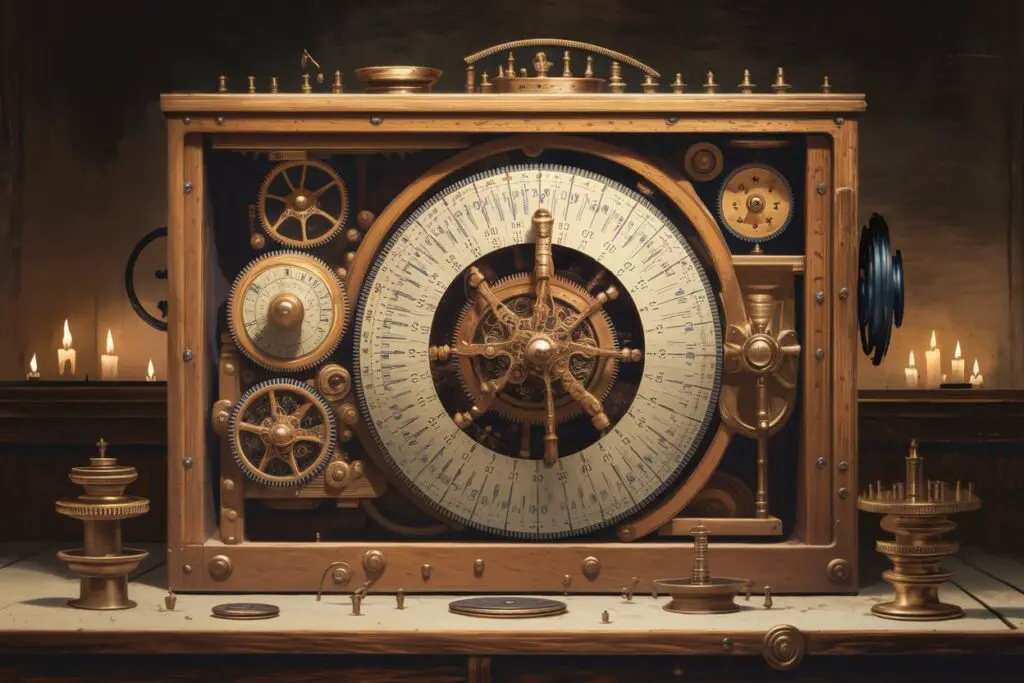

1.The Antikythera Mechanism—The World’s First Analog Computer

For centuries, historians believed that sophisticated mechanical computation was a modern invention. Then, in 1901, sponge divers off the Greek island of Antikythera stumbled upon a corroded bronze artifact that would rewrite history. Now known as the Antikythera Mechanism, this astonishing device—dating back to between 205 and 60 BCE—functions as the world’s first known analog computer, capable of predicting celestial events with remarkable precision. It was an engineering marvel centuries ahead of its time, demonstrating that the ancient Greeks possessed a level of technological sophistication previously thought impossible.

Housed in a wooden-framed case, the mechanism originally contained at least 37 bronze gears, with the largest measuring about 13 cm (5 inches) in diameter and featuring 223 teeth. These gears worked in harmony to track the movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets, allowing users to calculate eclipses and even determine the timing of the Olympic Games. The front of the device featured a zodiac dial, dividing the ecliptic into twelve sections representing the constellations—an invaluable tool for ancient astronomers.

Despite its advanced design, the Antikythera Mechanism remained a historical enigma for decades. It wasn’t until the late 20th century, with the aid of X-ray imaging and computer modeling, that researchers began to fully grasp its complexity. Today, fragments of the device are preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, while reconstructions—such as one built by the University College London Antikythera Research Team—demonstrate its original functionality. The existence of such a device suggests that it may have had undiscovered predecessors, hinting at a lost tradition of Greek mechanical engineering far more advanced than previously assumed.

The Antikythera Mechanism challenges our understanding of technological progress. It proves that ancient civilizations were capable of intricate scientific and mathematical achievements, rivaling those of much later periods. While no other devices of its kind have been found, its discovery raises a tantalizing question: What other forgotten innovations from the ancient world remain hidden beneath the sands of time?

2.Roman Concrete—A Building Material That Lasted Millennia

Roman concrete is one of the most remarkable engineering achievements of the ancient world, and its durability has baffled scientists for centuries. Unlike modern concrete, which degrades in a matter of decades, Roman structures such as the Pantheon and aqueducts have endured for over 2,000 years. So what was their secret? The answer lies in their unique mix of materials and an unexpected self-healing property.

The key ingredient in Roman concrete was pozzolanic ash, sourced from volcanic regions like Pozzuoli near Naples. This ash, combined with lime and water, created a chemical reaction that strengthened the material over time. But the real game-changer was a technique known as hot mixing—a process where lime was added at high temperatures, forming brittle lime clasts within the concrete. These clasts played a crucial role in the material’s longevity: when cracks formed, water would seep in, react with the lime, and trigger a recrystallization process that effectively repaired the damage. This self-healing mechanism allowed Roman concrete to withstand centuries of erosion, seismic activity, and even harsh marine environments.

Modern scientists, intrigued by its resilience, have studied Roman concrete in hopes of replicating its formula for sustainable construction. Research from MIT and Harvard has confirmed that the self-healing properties of Roman concrete could revolutionize modern infrastructure, reducing repair costs and extending the lifespan of buildings. While contemporary concrete relies on steel reinforcements that eventually corrode, the Romans’ approach—using natural, reactive components—proved far more enduring. Today, researchers are working to integrate these ancient techniques into modern materials, potentially changing the way we build for the future.

3.Greek Fire—The Mysterious Ancient Flamethrower

Few weapons in history have inspired as much fear and fascination as Greek Fire. Developed by the Byzantine Empire in the late 7th century CE, this incendiary weapon was unlike anything seen before. It could burn on water, adhere to surfaces, and was nearly impossible to extinguish—making it a devastating tool in naval warfare. The invention of Greek Fire is credited to Callinicus, a Greek engineer from Heliopolis, who fled to Constantinople after the Muslim conquests. His creation would prove instrumental in defending the Byzantine capital from multiple Arab sieges, including the First Arab Siege of Constantinople in 678 CE.

The exact composition of Greek Fire remains one of history’s best-kept secrets. Historians believe it was a mixture of petroleum or naphtha, sulfur, quicklime, and possibly potassium nitrate. Unlike conventional fire, it was deployed using pressurized siphons, allowing Byzantine ships to spray their enemies with streams of liquid flame. Some accounts even describe its use in handheld projectors (cheirosiphon), giving Byzantine soldiers an early form of flamethrower technology.

Greek Fire’s impact on warfare cannot be overstated. It gave the Byzantines a formidable advantage, allowing them to repel invaders and maintain naval supremacy for centuries. Despite numerous attempts by enemy forces to replicate its formula, the exact method of its production was a closely guarded state secret, passed down only to trusted individuals. By the 13th century, its use had declined, possibly due to the loss of knowledge surrounding its manufacture. Even today, modern scientists have been unable to recreate it with absolute certainty, solidifying Greek Fire’s place as one of the most enigmatic and advanced military technologies of the ancient world.

4.The Baghdad Battery—An Early Form of Electricity?

The Baghdad Battery is one of the most intriguing archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. Unearthed in 1936 near Khujut Rabu, close to the ancient city of Ctesiphon in modern-day Iraq, this 2,000-year-old artifact has sparked debate over whether ancient civilizations understood and harnessed electricity. The device consists of a small ceramic pot, a copper cylinder, and an iron rod, all sealed with asphalt. When filled with an acidic liquid like vinegar or lemon juice, the battery is capable of producing a small electrical charge—about 1.1 volts. But was it really used to generate electricity, or is this a modern misinterpretation?

Some historians and scientists believe the Baghdad Battery may have been used for electroplating—coating one metal with another using an electric current. This theory is supported by the discovery of ancient objects with thin layers of gold, which could have been applied using a primitive electrochemical process. However, no direct evidence, such as written records or other similar devices, confirms this use. Alternative explanations suggest that the artifact may have been a simple storage vessel or even had a religious function, as similar clay jars have been found containing scrolls rather than electrical components.

Unfortunately, the original Baghdad Battery disappeared in 2003 during the Iraq War, making further study impossible. While its true purpose remains uncertain, the mere possibility that ancient civilizations might have experimented with electricity challenges conventional historical narratives. Whether it was an early battery or not, the artifact highlights the ingenuity of ancient engineering and reminds us that history still holds many mysteries waiting to be unraveled.

5.The Aeolipile—Did the Ancient Greeks Invent the Steam Engine?

The Aeolipile, often credited to Heron of Alexandria in the 1st century CE, is considered the first recorded steam-powered device. While it never led to an industrial revolution in antiquity, its design demonstrated the basic principles of jet propulsion and rotational motion—concepts that would later become fundamental to steam engines. The device consisted of a hollow sphere mounted on a pivot, with two bent tubes allowing steam to escape. When heated, the escaping steam generated thrust, causing the sphere to spin. This simple yet ingenious mechanism showcased the potential of steam as a source of mechanical energy.

Though Heron described the Aeolipile in his work Pneumatica, earlier references to similar devices appear in the writings of Vitruvius, a Roman engineer from the 1st century BCE. However, despite its impressive demonstration of steam power, the Aeolipile was never developed into a practical machine. Instead, it remained a curiosity—likely used for temple demonstrations rather than industrial applications. It would take nearly 1,700 years before similar steam-powered technology was harnessed for practical use during the Industrial Revolution. The Aeolipile stands as a testament to the ingenuity of ancient engineers, revealing that the seeds of steam power were planted long before their full potential was realized.

6.Chinese Seismographs—Detecting Earthquakes in 132 CE

In 132 CE, the Chinese polymath Zhang Heng revolutionized earthquake detection with the invention of the Houfeng Didong Yi, the world’s first known seismoscope. At a time when earthquakes were mysterious and often attributed to supernatural forces, Zhang’s device provided emperors with a scientific method to detect seismic activity—an achievement nearly two millennia ahead of modern seismology.

The Houfeng Didong Yi was an intricately designed bronze vessel, resembling a large urn, adorned with eight dragon heads positioned around its circumference. Each dragon held a small metal ball in its mouth, while beneath them sat eight corresponding toads with open mouths. The mechanism inside the device, likely based on a suspended pendulum and lever system, responded to ground tremors by releasing a ball from the dragon facing the direction of the earthquake. This simple yet ingenious approach allowed officials to determine both the occurrence and approximate direction of an earthquake—an astonishing feat for the 2nd century.

One of the most remarkable demonstrations of its accuracy occurred when the device indicated an earthquake in the northwest. Initially, court officials doubted the reading, as no tremors had been felt in the capital. However, days later, a messenger arrived confirming a distant earthquake in Gansu province—over 400 miles away. This validation solidified Zhang Heng’s reputation as a visionary scientist and demonstrated the device’s effectiveness.

Although the original Houfeng Didong Yi has been lost to history, modern replicas based on ancient descriptions can be found in museums, including Beijing’s National Museum of China. Zhang Heng’s seismic detector laid the groundwork for future earthquake monitoring, proving that ancient Chinese technology was far more advanced than previously assumed.