The Glorious Afterlife Reserved for Fallen Warriors

For the Aztecs, death in battle was not an end but a gateway to a divine existence. Unlike commoners, who endured a grueling journey through Mictlān, warriors who perished in combat were immediately elevated to one of the most revered afterlives in Aztec cosmology. These fallen fighters were believed to accompany the sun god, Huitzilopochtli, on his daily journey across the sky. From dawn until midday, they marched alongside the blazing deity, ensuring the sun’s passage through the heavens.

After four years of celestial service, their spirits underwent a remarkable transformation. Warriors were thought to be reborn as hummingbirds or butterflies, flitting among the flowers and feeding on nectar—symbols of both renewal and the cyclical nature of life and death. This belief was not just religious doctrine; it was a powerful motivator for bravery in battle. Dying in combat was not a tragedy but an honor, a direct path to eternal glory.

This distinction set warriors apart from those who died of natural causes, who faced a long and arduous trek through the underworld. In contrast, warriors were immortalized, their spirits forever intertwined with the forces that sustained the world—a fate befitting those who had given their lives for the empire.

Journey to the Sun—The Warrior’s Role in the Solar Cycle

For the Aztecs, the afterlife was not a single, uniform destination but a complex system determined by the manner of death. Warriors who perished in battle or as sacrificial victims were believed to ascend to Ōmeyōcān, the paradisiacal realm of the sun god Huitzilopochtli. Their role in the afterlife was far from passive—they became companions of the sun, aiding its daily journey across the sky. This belief was deeply embedded in Aztec cosmology, where the sun’s movement was seen as a cosmic struggle requiring constant renewal through sacrifice.

Each day, from dawn until noon, the spirits of fallen warriors accompanied the sun as it rose in the eastern sky, shouting triumphantly and celebrating their eternal battle. At its zenith, these warriors relinquished their duty to the Cihuateteo, the spirits of women who had died in childbirth—another form of warriorhood in Aztec society. These women then guided the sun through the western sky until sunset, completing the celestial cycle.

This sacred duty was not eternal. After four years of service in the solar procession, warriors underwent a final transformation, returning to the earthly realm as hummingbirds or butterflies. These creatures, often associated with vitality and rebirth, symbolized the warriors’ continued presence in the world of the living. This belief reinforced the Aztec warrior ethos—death in battle was not an end but a glorious passage into a revered cosmic cycle, ensuring the sun’s survival and, with it, the continuation of life itself.

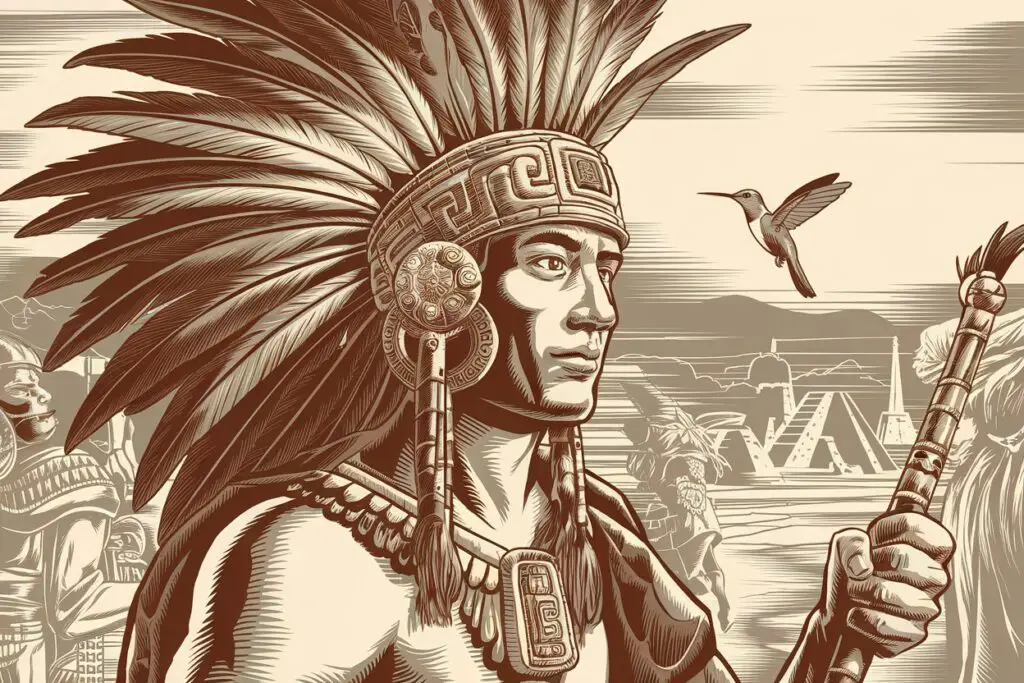

How Warriors Were Reborn as Hummingbirds in Aztec Belief

In Aztec cosmology, warriors who died in battle or as sacrificial offerings were believed to undergo a profound transformation: they were reborn as hummingbirds (huitzitzilin). This belief was deeply tied to the god Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec deity of war and the sun, whose name itself means “Hummingbird on the Left.” Warriors who perished in combat or on the sacrificial stone were thought to accompany the sun on its journey for four years before completing their metamorphosis into these sacred birds.

Hummingbirds held immense symbolic significance in Aztec culture. Their rapid movements and aggressive nature mirrored the qualities of a fierce warrior, while their iridescent feathers reflected the divine brilliance of the sun. The Aztecs saw these birds as celestial messengers, carrying the spirits of fallen warriors into the heavens. Women who died in childbirth—a battle of its own—were also believed to share this fate, reinforcing the idea that sacrifice and struggle led to a glorious rebirth.

This belief served not only as spiritual reassurance but also as a powerful motivator for warriors. Knowing that death in battle would grant them an eternal existence alongside Huitzilopochtli, many fought with extraordinary bravery, ensuring their place in the cycle of cosmic renewal.

The Connection Between Human Sacrifice and Eternal Honor

For the Aztecs, human sacrifice was far more than a brutal ritual—it was a sacred duty that maintained cosmic balance and ensured the continued existence of the universe. Central to their religious worldview was the belief that the gods had once sacrificed themselves to create humanity, and in return, humans had to offer their own lives to sustain the gods. Warriors played a particularly exalted role in this system, as their deaths in battle or through ritual sacrifice were seen as the highest form of honor.

Captured warriors, especially those taken in the ritualized “Flower Wars,” were prime candidates for sacrifice. Their blood was believed to nourish the gods, particularly Huitzilopochtli, the sun god, who required constant sustenance to continue his celestial journey. The process itself was highly ceremonial—victims were led to the top of a temple pyramid, where priests would extract their hearts using a sharp obsidian blade. This act was not seen as mere execution but as a transformation, granting the fallen warriors an esteemed place in the afterlife.

Unlike commoners, who often journeyed to Mictlān, a cold and arduous underworld, sacrificed warriors ascended to Ōmeyōcān, the “Place of the Dual Gods,” where they accompanied the sun in its daily path across the sky. This belief reinforced Aztec militaristic values, encouraging warriors to embrace death rather than fear it. Even foreign captives sacrificed in war were granted this posthumous honor, demonstrating the Aztecs’ profound reverence for martial valor. In this way, human sacrifice was not just a means of appeasing the gods but a pathway to eternal glory.

Differences Between the Afterlives of Warriors and Commoners

In Aztec cosmology, the afterlife was not determined by how one lived but by how one died. This belief system created stark contrasts between the fates of warriors and commoners after death. Warriors, particularly those who perished in battle or were sacrificed, were granted a privileged afterlife in Ōmeyōcān, the “Place of Duality,” ruled by the god of the sun and war, Huitzilopochtli. Here, they joined the sun on its daily journey across the sky, basking in eternal glory. After four years, these warriors were believed to transform into hummingbirds or butterflies, continuing their service to the gods by pollinating flowers and sustaining life.

In contrast, commoners who died of natural causes faced a more arduous fate. They were sent to Mictlān, the underworld governed by Mictlāntēcuhtli, the Lord of the Dead. Their journey to the afterlife was far from immediate; it spanned four years and required passing through nine treacherous levels, including crossing a vast river, navigating jaguar-infested terrain, and enduring obsidian-covered mountains. While this journey was not considered a punishment, it was undeniably grueling. Unlike warriors, commoners did not receive celestial honors but instead faded into the depths of the underworld.

Women who died in childbirth, however, were exceptions among commoners. They were honored similarly to warriors, believed to aid the sun’s descent after noon. Likewise, individuals who perished by drowning, lightning, or disease associated with the rain god Tlaloc were sent to Tlālōcān, a paradise where they enjoyed eternal abundance. These distinctions highlight the Aztecs’ emphasis on death’s circumstances over life’s deeds, reinforcing their warrior-centric societal values.

The Role of Mythology in Shaping the Warrior’s Fate

Aztec mythology played a fundamental role in defining the fate of warriors after death, embedding their destiny within the grand cosmic order. According to Aztec beliefs, warriors who perished in battle or as sacrificial captives were granted a privileged afterlife. Rather than facing the arduous trials of Mictlān—the underworld reserved for those who died of natural causes—fallen warriors were believed to ascend to Ōmeyōcān, the paradisiacal realm ruled by Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun. This divine association reinforced the idea that warfare was not only a means of earthly glory but also a sacred duty that ensured eternal honor (source: Curationist).

Mythology further shaped the warriors’ fate through their transformation after death. For four years, their spirits were thought to accompany the sun on its daily journey across the sky, aiding Tonatiuh, the solar deity, in his eternal battle against darkness. After this period, they were reborn as hummingbirds or butterflies, symbols of renewal and vitality. This metamorphosis underscored the belief that warriors continued to serve the gods even in death, reinforcing the valorization of martial sacrifice.

The myth of Huitzilopochtli himself exemplified the warrior’s sacred role. Born fully armed to defend his mother, Coatlicue, from his rebellious siblings, Huitzilopochtli embodied the ideal Aztec warrior—relentless, fearless, and divinely ordained. His ceaseless struggle against cosmic forces mirrored the earthly battles of Aztec fighters, who saw themselves as extensions of this divine conflict. By dying in combat, warriors ensured not only their own exalted afterlife but also the continuation of the universe itself, as the gods’ sacrifices were believed to sustain cosmic balance.

These mythological narratives were deeply woven into Aztec society through ritual enactments and oral traditions that reinforced their significance. Ceremonies, songs, and poetry celebrated the warrior’s fate, instilling a cultural ethos that glorified bravery and sacrifice. This belief system motivated warriors to embrace combat without fear, knowing that their deaths would secure them a place among the celestial forces guiding the sun. In this way, mythology did not merely explain the warrior’s afterlife—it actively shaped the Aztec worldview, ensuring that warfare remained a sacred and honored pursuit throughout their civilization.

How These Beliefs Inspired Bravery and Fierceness in Battle

For the Aztecs, courage in battle wasn’t just a matter of personal honor—it was a sacred duty, intimately tied to the cosmos. Warriors believed that dying in combat was the surest way to attain a glorious afterlife, where they would either join the sun god Tonatiuh in his celestial journey or be reborn as hummingbirds and butterflies, feeding on the nectar of divine flowers. This belief removed the fear of death, transforming battle into a spiritual opportunity rather than a mortal risk. It wasn’t just about victory; it was about securing an eternal place in the cosmic order.

This ideology shaped the Aztec military ethos, making their warriors some of the fiercest in Mesoamerica. Since the afterlife was determined by the manner of death rather than moral conduct, warriors sought to die heroically in combat rather than perish from disease or old age, which would send them to the grueling underworld of Mictlān. In this worldview, death on the battlefield was not an end but a transition to a higher existence. This belief also encouraged the capture of enemies rather than outright killing them—captured warriors were destined for ritual sacrifice, an act seen as an offering to the gods that ensured the continuation of life itself.

The psychological impact of these beliefs cannot be overstated. Aztec warriors fought with unmatched ferocity, knowing that their fate in the afterlife was directly tied to their bravery. Retreat was dishonorable, and surrender was often a deliberate choice rather than an act of desperation—it meant an honorable death in the sacrificial rituals that sustained the gods. Even when facing overwhelming odds, Aztec warriors stood their ground, driven by the certainty that their sacrifice would keep the universe in balance. This relentless warrior spirit was a key factor in the expansion of the Aztec Empire, allowing it to dominate large portions of Mesoamerica before the arrival of the Spanish.