River Crossings—Wagons, People, and Animals Swept Away

River crossings on the Oregon Trail weren’t just logistical hurdles—they were deadly gambles that turned tranquil landscapes into scenes of chaos and loss. For thousands of emigrants heading westward during the mid-19th century, these crossings posed one of the most immediate and terrifying threats to survival. The rivers themselves—like the Kansas, Snake, Green, and North Platte—were unpredictable, swollen by spring snowmelt or sudden rainstorms, and strong enough to sweep away entire families, wagons, and oxen in seconds. One particularly grim incident in 1850 saw 37 people drown while trying to cross the Green River, underscoring just how quickly a misjudgment could turn fatal (OCTA Trail Association).

Pioneers had a few options, none of them safe. Fording the river—driving the wagon straight through—was common but perilous; the current could stall or overturn the wagon, trapping people inside. Ferries, when available, were safer but often overpriced and unreliable. Some tried caulking their wagons and floating them across, a method that demanded precision and luck. Even a minor shift in balance could send an entire family’s worldly possessions into the current. Animals, too, often panicked midstream, either drowning or injuring their handlers in the frenzy (NPS.gov).

Beyond the physical danger, river crossings exacted a heavy emotional toll. Travelers spoke of the haunting sight of wagons and bodies disappearing downstream, sometimes within view of helpless onlookers. Survivors often emerged from the water missing food, tools, or medicine—supplies that couldn’t be replaced in the wilderness. These crossings didn’t just test frontier ingenuity—they were moments of existential risk, where one wrong decision could erase months of preparation and cost lives. In a journey filled with uncertainty, the rivers stood out as unpredictable enemies, claiming more than their fair share of victims along the trail.

Disease and Illness—Cholera, Dysentery, and Lack of Medical Care

If there was one invisible killer that haunted every mile of the Oregon Trail, it wasn’t wolves, raiding parties, or even starvation—it was disease. Among the most feared was cholera, a bacterial infection that turned a thriving camp into a deathbed in mere hours. Caused by Vibrio cholerae and spread through contaminated water, cholera outbreaks became especially lethal during peak migration years like 1850, when thousands of gold-seekers and settlers crowded the Trail. Symptoms struck with terrifying speed—severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration that could kill within a day. And with sanitation systems virtually nonexistent, one infected water source often spelled disaster for entire wagon trains, particularly along the Platte River’s banks, a notorious hotbed for outbreaks.

But cholera wasn’t the only threat. Dysentery—often dubbed “the bloody flux”—was another gastrointestinal tormentor, fueled by spoiled food, decaying carcasses, and poor hygiene. Typhoid fever, too, lurked in the background, spread by the same unsanitary conditions. The real kicker? Most emigrants had little more than folk remedies and patent medicines to fight these ailments. Medical kits might include castor oil, opium, or even mercury-based calomel—treatments that often did more harm than good (OCTA).

Few wagon trains had trained doctors, and those that did often relied on outdated or dangerous practices like bloodletting. Even quinine, one of the few somewhat effective medicines, was in short supply. Respiratory infections, mountain fever (likely tick-borne), scurvy from vitamin C deficiency, and childhood diseases like measles and smallpox also swept through camps, especially during long stops or rest days. The result? An estimated 65,000 deaths over 25 years, many of them due to illness (source).

In the end, disease wasn’t just a hazard—it was a grim certainty. The Oregon Trail may have promised a new life, but for tens of thousands, it delivered an early grave.

Harsh Weather—Blizzards, Heatwaves, and Sudden Storms

The Oregon Trail may conjure images of rolling plains and sun-drenched wagon trains, but the reality was far more brutal—especially when it came to the weather. Pioneers didn’t just battle distance; they fought the sky itself. From scorching heat to bone-cracking cold, the elements were often merciless and, in many cases, deadly. In fact, weather-related hazards ranked among the most unpredictable and lethal threats emigrants faced during their westward journey.

Blizzards posed a catastrophic risk, particularly in high elevations like the Rockies and the Blue Mountains. A chilling example occurred in 1856, when a late-season Mormon handcart company was overtaken by snowstorms in central Wyoming. More than 200 of the nearly 1,000 travelers perished in subzero temperatures—many from hypothermia and frostbite. Even in milder seasons, sudden snow squalls could trap entire wagon trains, leaving families stranded with dwindling supplies.

But if cold could kill, so could heat. Crossing the Great Plains and eastern Oregon’s desert stretches exposed pioneers to temperatures well above 100°F (38°C). Sunstroke, dehydration, and blistered skin were common. The heat even warped wagon wheels, forcing travelers to soak them in rivers overnight to prevent the wood from shrinking and splitting .

Then there were the storms—violent, sudden, and often terrifying. Thunderstorms could unleash hailstones the size of apples, injuring both people and livestock. Lightning strikes killed at least six documented travelers, and tornadoes occasionally tore through campsites, scattering supplies and crushing wagons. Metal tools and firearms became lightning rods during these weather events, increasing the danger.

Flooding presented a double-bind: too little rain meant drought and dust storms, while too much turned trails into muddy death traps and rivers into raging torrents. Dust could become so thick that pioneers smeared axle grease on their lips to prevent them from cracking open.

Weather on the Oregon Trail wasn’t just a backdrop—it was an active, often deadly player in the story of westward expansion. And unlike other dangers, it offered no negotiation and no reprieve.

Accidents on the Trail—Runaway Wagons and Firearm Mishaps

The Oregon Trail might conjure images of sweeping plains and stoic pioneers, but the truth on the ground was far grimmer—and often bloodier. Accidents were a silent killer on the trail, lurking not in the shadows of mountain passes or hostile encounters, but in the everyday mechanics of frontier travel. Runaway wagons and firearm mishaps were two of the deadliest culprits, and they claimed thousands of lives in ways that were as sudden as they were tragic.

Runaway wagons were a constant threat. With each wagon weighing over 2,000 pounds when fully loaded, even a momentary loss of control—especially on steep descents or uneven terrain—could spell disaster. Children were particularly vulnerable; many were crushed beneath wagon wheels after falling while climbing in or out of the moving vehicles. According to the National Park Service, being run over was one of the most common accidental deaths along the trail.

Firearms, though essential for hunting and protection, proved equally lethal. In an era without standardized gun safety, accidental discharges were frighteningly common. Many pioneers were injured—or killed—while cleaning their rifles, crossing rough terrain with loaded weapons, or simply mishandling firearms during moments of fatigue. In fact, firearm accidents ranked as the second leading cause of accidental death on the trail, right behind wagon-related injuries.

But the danger didn’t stop there. Stampeding oxen, falls from wagon benches, and injuries while managing draft animals added to the grim tally. And with little to no access to medical care, even a broken bone or a deep cut could become a death sentence. As the Oregon-California Trails Association notes, many of the estimated 65,000 emigrants who died over the 25-year span of the trail’s use perished not from dramatic battles or starvation, but from these unglamorous, everyday hazards.

In a journey already defined by hardship, it was often the smallest misstep—a slip on a wagon tongue, a careless reach for a rifle—that proved fatal.

Starvation and Dehydration in Isolated Terrain

Starvation along the Oregon Trail wasn’t the headline killer—but it was always lurking in the background, especially when emigrants found themselves stranded in remote, unforgiving terrain. While diseases like cholera and dysentery claimed more lives overall, hunger and thirst often pushed pioneers to their physical and emotional limits. The threat became particularly acute in barren regions such as the Snake River Plain or the parched stretches of the Great Basin, where food for both humans and draft animals was in dangerously short supply. When oxen and mules began to collapse from lack of forage, wagons stalled, and the domino effect could be catastrophic.

The psychological toll of dwindling provisions was as corrosive as the physical one. Delays caused by river crossings, mechanical failures, or illness often meant overlanders burned through their rations faster than planned. In such moments, desperation bred grim decisions. The 1860 Utter-Van Ornum wagon train, for example, was ambushed and left stranded with no food. Four children died of starvation, and in a harrowing turn, survivors resorted to cannibalism at what became known as Starvation Camp.

Water scarcity only intensified the crisis. Many emigrants had to travel 20 to 40 miles between water sources, only to find alkaline springs or stagnant pools. Dehydration, worsened by heat and disease, became a silent killer. As OCTA notes, contaminated water often led to deadly gastrointestinal illnesses that further weakened travelers already on the brink. In the end, starvation and dehydration rarely killed outright—but they eroded the resilience of both people and animals, leaving them vulnerable to the harsher fates that so often marked the trail.

Wagon Malfunctions and Broken Axles in Rough Country

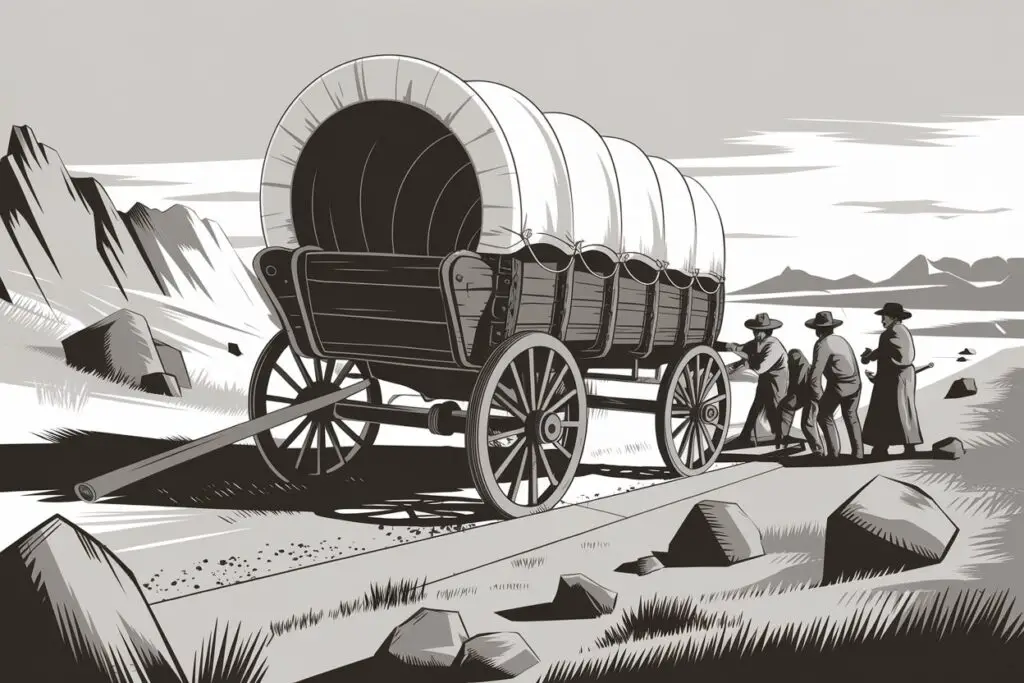

Wagon malfunctions weren’t just inconvenient—they could be catastrophic. As thousands of emigrants bumped along the 2,000-mile Oregon Trail, the very vehicles carrying their hopes—and everything they owned—were pushed to the brink. Most pioneers used a type known as the “prairie schooner,” a deceptively simple wooden vehicle about 11 feet long and 4 feet wide, built from hardwood and iron. But here’s the rub: these wagons were never designed for mountain passes, river fords, or the punishing ruts carved into the high plains. With only a single set of springs under the driver’s seat, the ride was bone-jarring at best—and at worst, destructive.

The most feared failure was a broken axle. Axles, often made of hickory or oak, bore the brunt of every jolt and jostle. One bad bounce over a rocky incline or during a river crossing could snap an axle clean in two, immobilizing the wagon instantly. According to the Oregon-California Trails Association, pioneers often carried spare axles and wheels, but even then, repairs were grueling and supplies limited (source).

And get this—wooden wheels could literally fall apart if not maintained. The dry air of the plains caused the wooden spokes to shrink, loosening the iron rims. To prevent disaster, travelers soaked their wheels in rivers overnight, hoping the swelling wood would hold for another day’s march. Still, many wagons were abandoned mid-journey, stripped of usable parts or left behind after families were forced to lighten their loads. In some cases, people were injured—or killed—by collapsing wagons or falling beneath heavy wheels, a grim reminder that even the most mundane technology could be deadly in the wilderness (NPS.gov).

Wagon maintenance became a daily ritual. Those with carpentry or blacksmithing skills were invaluable, and those without? They gambled with every mile. The constant threat of mechanical failure added to the psychological toll of the journey, as each creak or groan of timber could spell disaster. For pioneers, surviving the Oregon Trail wasn’t just about endurance or luck—it was about keeping the wheels turning, literally.

The Psychological Toll—Loneliness, Fatigue, and Mental Strain

The Oregon Trail wasn’t just a test of physical endurance—it was a psychological crucible that reshaped the inner lives of thousands. While tales of broken axles and cholera outbreaks often dominate the historical narrative, the emotional toll of the journey was equally punishing, if not more enduring. Emigrants left behind homes, family, and the familiar rhythms of settled life to face months of uncertainty across a vast and often unforgiving landscape. That sense of isolation was more than metaphorical. For many, especially women, the trail became a place of haunting dreams and silent dread. Diaries from the period describe recurring nightmares—wolves stalking the wagons, children lost to the prairie, or sudden ambushes that never came but always loomed large in anxious minds.

Psychological fatigue wasn’t just about fear—it was also about decision fatigue. Every day brought hard choices: which route to take, what to leave behind, how to care for the sick or bury the dead. The emotional weight of discarding heirlooms to lighten the wagon or watching a neighbor succumb to cholera added layers of grief and guilt. According to the Oregon-California Trails Association, over 65,000 people died during the westward migration—each loss a trauma absorbed by those left to trudge onward (OCTA).

Despite this, the trail also forged intense social bonds. Travelers formed joint-stock companies with constitutions to govern behavior and resolve disputes, creating micro-societies that offered emotional scaffolding amid the chaos. As noted by the National Park Service, these impromptu communities helped alleviate the crushing loneliness, especially in the absence of structured mental health care. Still, for many, the trauma didn’t end when they reached Oregon. Survivors often carried the scars for life—what we might now recognize as symptoms of PTSD. The Oregon Trail wasn’t just a migration; for many, it was a psychological reckoning.