Gladiator Blood as a Cure for Epilepsy

In ancient Rome, few medical treatments were as bizarre—or as gruesome—as the belief that drinking gladiator blood could cure epilepsy. This practice, rooted in superstition rather than science, stemmed from the idea that the vitality and strength of these warriors could be transferred to the afflicted. Gladiators were seen as paragons of physical endurance, and their blood was thought to contain a life force strong enough to counteract the mysterious seizures associated with epilepsy.

The treatment involved collecting the warm blood from a fallen gladiator immediately after death and consuming it, raw. Some accounts even suggest that parts of the gladiator’s liver were eaten for the same supposed medicinal properties. Roman physicians, influenced by humoral theory, believed that epilepsy was caused by an excess of “cold” humors in the body. Since blood was associated with heat and vitality, drinking it was thought to restore balance. Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist and author of Historia Naturalis, documented this practice, though even he expressed skepticism about its effectiveness.

When gladiatorial combat was banned in the early 5th century AD, the desperate search for a cure led to an equally macabre substitute: the blood of executed criminals. This continuation highlights how deeply ingrained the belief was, despite a lack of real medical efficacy. Today, of course, we understand that epilepsy is a neurological disorder, and the notion of drinking human blood as a cure is both scientifically unfounded and ethically horrifying. But in ancient Rome, when medicine often blended with magic and ritual, such treatments were not just accepted—they were sought after.

Drinking Ground-Up Mice to Treat Ailments

Ancient Roman medicine was a curious blend of empirical observation, superstition, and sheer desperation. Among the more bizarre treatments was the consumption of ground-up mice, a remedy that Pliny the Elder documented in his vast encyclopedia, Historia Naturalis. According to Pliny, boiled or pulverized mice were prescribed particularly for children suffering from incontinence. The logic? A mix of sympathetic magic and rudimentary pharmacology—Romans believed that consuming an animal with perceived bodily resilience could transfer its qualities to the patient.

This was not an isolated case of animal-based medicine in Rome. Similar treatments included using wolf liver to ward off sickness or consuming parts of exotic creatures for various ailments. The use of mice highlights the experimental, if misguided, nature of ancient Roman healing practices. Without a modern understanding of disease, Roman physicians relied on trial and error, leading to remedies that seem shocking today. While this treatment would be dismissed outright by contemporary medicine, it serves as a fascinating glimpse into the unconventional and frequently grotesque world of ancient healthcare.

Using Spider Webs as Bandages for Wounds

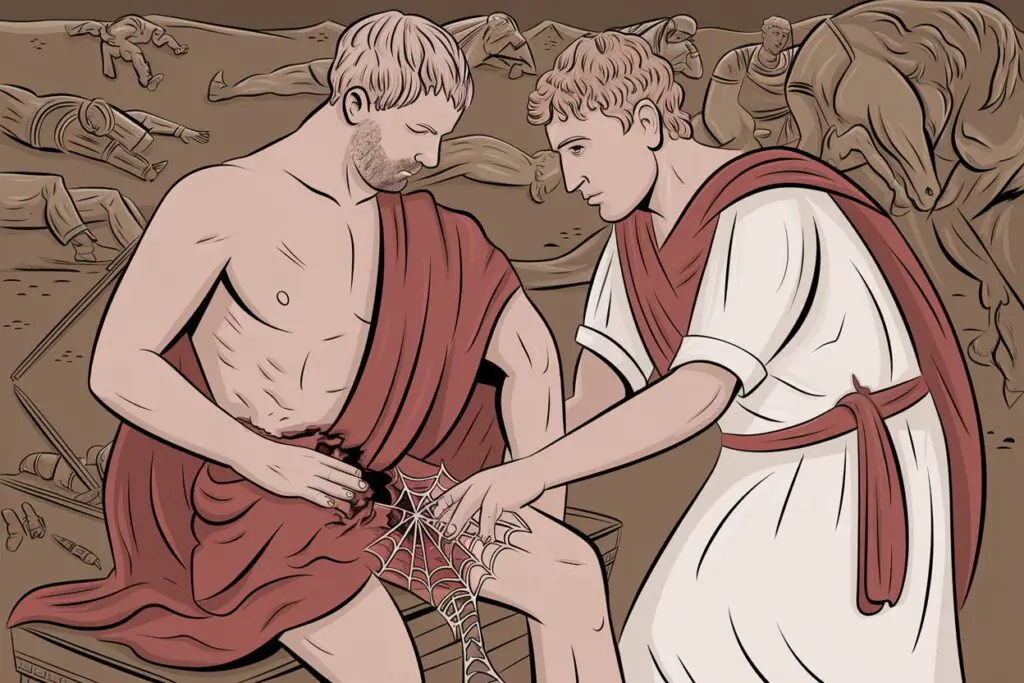

Ancient Roman medicine was a fascinating blend of practical observation and deeply rooted superstition. Among their more unusual remedies was the use of spider webs as bandages for wounds. Roman physicians believed that spider silk had natural antiseptic and anti-fungal properties, making it an effective material to prevent infections. Moreover, some suggested that spider webs contained vitamin K, a crucial factor in blood clotting, which could help stop bleeding more efficiently. Soldiers and gladiators, frequently suffering from cuts and gashes, may have relied on this peculiar treatment to accelerate healing on the battlefield.

To apply the remedy, Roman healers would gather spider webs, mixing them with honey or vinegar to enhance their supposed antibacterial effects. The soft, fibrous texture of the webs helped absorb moisture and provided a protective covering over wounds. While modern research has questioned the true antimicrobial properties of spider silk, the idea of using it for medical purposes has inspired innovations in artificial spider silk. Presently, scientists are developing ultra-strong, biocompatible, and biodegradable bandages modeled after this ancient practice. Though the Romans lacked modern medical knowledge, their resourcefulness in using natural materials remains a testament to their ingenuity.

Powdered Wolf Liver to Ward Off Sickness

Ancient Roman medicine was an unusual mix of practical remedies, religious rituals, and outright superstition. One particularly bizarre treatment involved the use of powdered wolf liver as a cure for various ailments. The Romans, like many ancient civilizations, believed that consuming parts of certain animals could transfer their innate strengths to humans. Wolves, revered for their endurance and hunting prowess, were thought to possess powerful medicinal properties. Physicians and healers would dry and grind the liver into a fine powder, which was then mixed with liquids such as wine or water for ingestion.

This strange remedy was believed to treat a surprising range of conditions, including epilepsy, vertigo, edema, and even syphilis. Some medical practitioners also prescribed it for migraines and dysentery, reflecting the widespread belief in the liver’s curative properties. However, there was no scientific basis for its effectiveness—like many Roman treatments, it relied more on symbolic thinking than empirical evidence. The use of animal organs in medicine was not unique to Rome; similar practices existed in Greek and medieval European traditions. While modern medicine has long abandoned such remedies, they offer a fascinating glimpse into how ancient societies attempted to understand and combat disease.

Fasting and Eating Raw Onions for Mental Clarity

The ancient Romans believed that mental clarity and physical well-being were deeply interconnected, and their medical practices frequently reflected this philosophy. Among the more unconventional treatments was the combination of fasting and consuming raw onions, a regimen thought to sharpen the mind and cleanse the body. While this practice may seem peculiar today, it was rooted in broader ancient traditions that linked diet to cognitive function.

Fasting was a common practice in many ancient cultures, including Greece and Rome, where it was believed to purge impurities and enhance mental acuity. Philosophers such as Pythagoras and Roman Stoics like Seneca advocated for periods of fasting, arguing that abstaining from food could lead to clearer thinking and greater self-discipline. The Romans, influenced by these ideas, likely saw fasting as a way to reset the body and mind, making it a natural component of their medical treatments.

Raw onions, meanwhile, were valued for their supposed medicinal properties. Rich in antioxidants and believed to have anti-inflammatory effects, onions were commonly used in Roman cuisine and medicine. Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia, documented various uses of onions, including their role in treating ailments and enhancing vitality. The Romans may have considered raw onions a natural stimulant, capable of boosting alertness and cognitive function, particularly when combined with fasting.

Though modern science does not fully support these claims, contemporary research does suggest that fasting can improve brain function by promoting autophagy and increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports neural growth. Onions, too, contain compounds that may have health benefits, including improving circulation and reducing inflammation. While the Romans lacked a scientific understanding of these mechanisms, their intuition about the link between diet and cognition was not entirely unfounded.